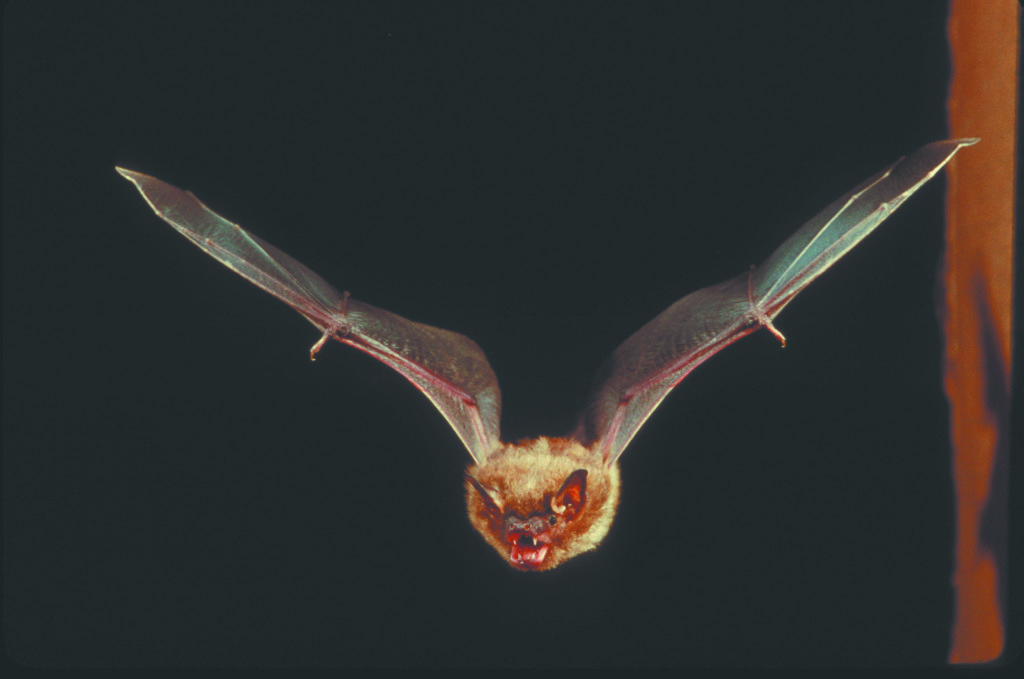

While bats may be scary creatures many associate with the Halloween season, the flying mammals are an essential part of the region’s ecosystem according to former R.B. Winter State Park educator Emily Embick.

“They keep our insect populations under control, with some species eating nearly a million insects per year,” she said.

Mike Scafini, an endangered mammal specialist with the bureau of wildlife management within the Pennsylvania Game Commission, admitted that bats help keep unwanted spiders and mosquitoes at bay. If the bats become extinct, these insects will be a major problem to all.

However, white nose syndrome is wiping out countless bats throughout central Pennsylvania, and wildlife agencies are struggling to find the solution.

There are nine species of bats in Pennsylvania, said Embick.

These include little brown, Indiana, eastern small-footed, northern long-eared, big brown, tri-colored (also known as the pygmy or the eastern pipistrelle), silver-haired, eastern red and the hoary bat.

“There are also two species that are rare visitors from the south, the seminole and the evening bat,” Embick said. “Six of our bat species are true hibernators and three species (hoary, red and silver-haired bat) migrate south in the winter.”

Fatal fungus

The six hibernating species common to most of Pennsylvania are of the greatest concern for contracting white nose syndrome, according to Mike Scafini.

White nose syndrome is a “cold-moving fungus that is found only in caves and mines,” he said.

Embick added that the syndrome is white in color and grows on the muzzles and wing membranes of bats.

“The fungus only affects bats during hibernation because it is a cold-thriving fungus,” Embick said.

Temperatures are typically needed to be just above freezing, or in the 35–degree range for the fungus to grow, Scafini said, and theories exist that it can maintain growth into the low 40s.

“But it doesn’t survive above or below those temperatures,” Scafini added.

The actual fungus isn’t the killer, Scafini said. It is the effect of the fungus that impairs a bat’s natural responses.

“While they are hibernating, the fungus irritates them and wakes them up twice as much,” Scafini said.

It’s utter confusion to a bat who is supposed to be sleeping inside its cave or mine during brutally cold weather and suddenly he is awakened as if it were spring.

“They wake up and they’re dehydrated. What essentially kills them is the loss of that fat reserve,” Scafini said.

Who is at risk

The six types of hibernating bats in the state that are impacted currently include the little brown bat, northern long-eared bat, Indiana bat, small-footed bat, silver-haired bat, tri-colored bat and the big brown bat.

“Currently, the Indiana bat is listed as federally endangered,” Embick said. “The northern long-eared is listed as threatened and the small-footed is a species of special concern.”

Scafini said the eastern small footed bat tends to reside in a “rocky palace, along slopes and crevices” because they are tiny.

Little browns and big browns, Scafini said, enjoy hollow trees and bat boxes, too.

Growing concern

It’s the little browns, Scafini said, that are declining in number by 99 percent, while others are also seeing declining amounts.

“White nose syndrome surfaced in PA in 2008 and began killing cave bats in 2009,” Embrick said. “Since then, we have seen a 99-percent decrease in cave dwelling bat populations throughout the state.”

Scafini said the syndrome made its way here from Europe’s cave bats, and at first hibernating bats in the United States did not see an impact.

Over time, however, the fungus left by bats on the surfaces of rocks in the caves and other hibernating spots grew to irritate the populations that sleep during the cold months.

“There are many conservation efforts happening throughout the state,” Embrick said. “Surveying populations, studying treatment options of white nose syndrome, citizen science programs and general public awareness of the importance of bats.”

Scafini said the bat population is at the top of his department’s priority list. Surveys are conducted over three to five years as bat boxes are placed throughout the state to provide an alternative space for hibernation.

“In winter and spring, we are trapping and doing bat box counts. We trap and take photos,” Scafini said.

By using ultraviolet light in photos, the scientists can see spots on the bats that otherwise wouldn’t be visible with the naked eye.

“If it shows up orange, there are fungal spores,” Scafini said.

The bats swarm and mate in the spring. Most are ready to start hibernation in October, according to Scafini, and all bats are in hibernation by December.

“By early April, they start exiting,” he said.

When the bats are trapped, Scafini said, the scientists put a band on each one with an identification number in order to retrace its history.

“We have been tracking the northern long ear bats with transmitters to see where they are nesting,” he said.

Currently, a large population has been studied residing in a swamp by Bald Eagle State Park. There is a lot of brush and thick shrubs scientists travel through to get to the bats, Scafini said.

A solution to remove the fungus is being tested.

An application of polyethylene glycol “tricks the fungus,” Scafini said. “And the fungus thinks the water is stressed and it doesn’t grow.”

“We are trying it in a tunnel in Clearfield County,” Scafini said, by spraying it with the substance and observing the fungus’ reaction.

Scafini said he hopes to see results from this winter in 2019 as they pull the bats down, photograph them and take swabs to see if the spores decrease.

In the meantime, Embrick urged readers to become more proactive in the battle against white nose syndrome

“Don’t let the efforts to save the bats up to scientists,” she said. “If you would like to know how you can get involved with the conservation efforts in the state or you just want to know more, contact your local state park to see if it is offering programs or has more information for you.

“You can also visit the Pennsylvania Game Commission website where you can find more information on particular species of bats, white-nose syndrome, creating bat boxes, as well as information on how to safely remove bats from your home.”