Today, Charlie Steininger, 96, and Charles “Chuck” Ticknor, 93, live in the same Snyder County town. In 1945, they stood on separate ships watching United States Marines attacking the Japanese-held island of Iwo Jima.

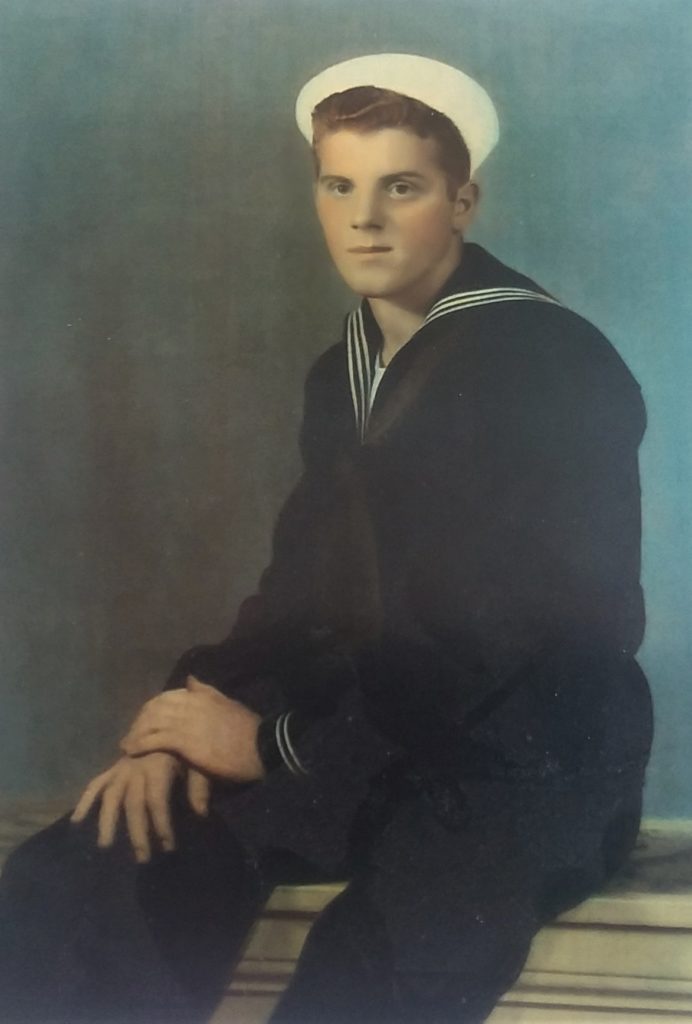

In 1943, Steininger and his two brothers traveled to Harrisburg to enlist in the Navy. While there, a loudspeaker called for volunteers to join the Army or Marines. After a while, an officer approached the brothers and said, “Gene Steininger, you’re going to the Army. John Steininger, you’re going to the Marines. Charles Steininger, you’re going to the Navy.”

Charlie Steininger ended up assigned to the USS Texas, the oldest battleship in the Navy at the time and one that had fought in WWI. Steininger was a pointer on a quad 40 mm anti-aircraft gun. He served in Guam, Iwo Jima, Okinawa and the Philippines. Both he and his brothers eventually returned home to Pennsylvania.

A Wikipedia entry says the USS Texas “spent just three days pounding the Japanese defenses on Iwo Jima in preparation for the landing of three Marine Corps Divisions.” What the entry fails to portray is the men on that ship, gripping their guns and concentrating on their targets.

“We bombarded it for two solid days and half a night,” Steininger said. Explaining that every third shot was a lit-up tracer, he added that the nighttime attack had so many shots flying through the air, “It looked like daylight.”

Brush with death

Standing on an LSM 32 (Landing Ship Medium), Chuck Ticknor, then 18 and a second loader on a 40 mm gun, watched mortar shells from U.S. ships pummeling the island until his captain shouted from the tower, “Ticknor, you better get your head down or you’re gonna get it blown off!”

Ticknor dove for cover.

“I didn’t know, once we got in far enough, it wasn’t just ours going in,” he said of the mortars. “It was theirs going out.”

By the time the chaos ended, the place where he’d been standing was riddled with bullet holes. He later told his sister, Wanda, “I may never get to heaven, but I once came mighty close.”

“It was fun up until I realized how serious it was,” he said.

Beach battle

The ships bombing Iwo Jima were supposed to prepare the island for the Marines to attack. They had no way of knowing, however, the Japanese soldiers were hunkered down in a labyrinth of bunkers, waiting out the bombs.

Ticknor had talked with one of the Marines who, happy to see the bombing of the island, said, “Boy, we’re finally getting an easy one.”

“He thought it would be easy, but it ended up being the worst of all of them,” Ticknor said.

“They didn’t figure on the bank. They thought it’d be a flat beach,” Ticknor said, adding with a shake of his head, “They were just sitting ducks there.”

The beach filled with dead Marines while the wounded made their way back to doctors on the ships.

“The thing I remember, too, you could smell it,” Ticknor said. “Can you imagine? A thousand dead bodies on the beach?”

Flag on Iwo Jima

Watching from the USS Texas, Steininger also saw the terrible price paid for Iwo Jima

“Come 4 o’clock in the afternoon and all you saw was bodies not moving, you knew something happened,” he said.

Much later, Steininger learned that he knew one of the injured Marines.

“When the invasion went on, I didn’t know it but my brother (John) went in,” he said. “He got shot through the knee, and they sent him home.” John eventually had an artificial knee replacement.

With his buddies on the ship, Steininger witnessed one of the iconic moments in the Battle of Iwo Jima when six Marines raised a U.S. flag on top of Mount Suribachi.

“It made the chills go up your back,” he said. “Yeah, that was something, to see that flag going up. There were cheers going up all over.”

Taking care of business

The USS Texas also served during the Battle of Okinawa.

“You should have seen the sky that night,” Steininger said. “I bet you there were 500, 600 airplanes flying around. Ours and the Japanese.”

His job was to fire his gun at a point ahead of enemy planes, allowing them to fly into the flak at the precise moment for impact. Asked about fear, Steininger shook his head.

“You didn’t think of that. That was the least of your worries,” he said. “You just took care of your business.”

During the battle, sailors on the USS Texas saw a downed Japanese pilot floating in the water and pulled him onboard. In disrobing him to make sure he didn’t have a grenade strapped to his chest, the men were surprised to see his torso wrapped in purple silk — Japanese kamikaze pilots were given a funeral before their mission because they were not expected to return alive.

“When they unwrapped the silk, a New Testament and a photo of his wife and two children fell to the floor,” Steininger said. “That was something to behold. I think every officer there, well they were at a loss for words. The Japanese, you never thought they had any religion at all in them.”

The pilot was eventually sent to an American POW camp in Connecticut.

“I often wondered what happened to him,” Steininger said.

Celebrating the end

The USS Texas was in the Philippines when the sailors learned the Japanese had surrendered aboard the USS Missouri — just in time to stop the Texas from being sent to Tokyo for its next mission.

“There was a cheering and a carrying on,” Steininger said of the sailors’ reactions. And of his own reaction, he shrugged and said, “Like everyone else: When are we going home?”

Within a day or so, the Texas headed for California, carrying a shipload of relieved, grateful sailors who had served their country and could now return to their families.